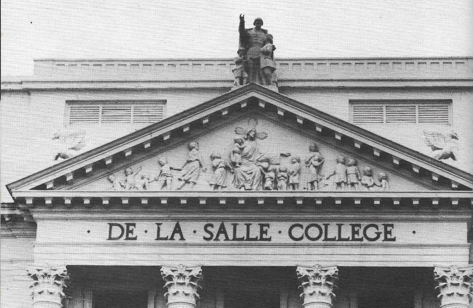

To reminisce, the yesteryears of classmates, teachers, and episodes of campus life that had become very much a part of our lives. De La Salle College was a close knit campus where everybody knew everybody. Most of us had moved up from grade school comprised by three sections to high school of four sections. Some classmates had siblings in other levels. The Taft population was relatively small and tight-knit, consisting of some three thousand students in all so hardly anyone was a stranger in a school that was still a College and not a University. We were told that De La Salle College meant a well-rounded Christian education from its motto: Religio, Mores Cultura. In grade seven Bro. Felix, our principal, revealed why St. John Baptist de la Salle atop the school’s facade points to the East: “Boys, over there is St. Scholastica.”

Being all boys’ school, classes tended to be rowdy. Almost every classroom had a class jester; even the A sections were not exempt from some kind of tom-foolery. The mischief was infectious and typical throughout high school classes. To keep us in line the Christian Brothers specially the principal, who were from reformatory schools in the US, did not spare the stick – sometimes a fist – to instill discipline. Testing the limits of each teacher’s patience was like playing a dangerous game that could result in being sent to the principal’s office.

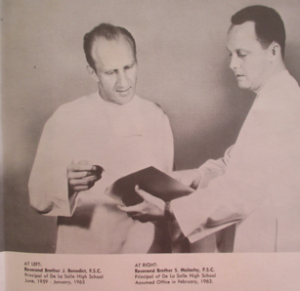

We went through three high school principals. Our first, Bro. Benedict had a way of dealing with miscreants with a swift kick in the butt, much like a mule’s kick with the full force of the sole – more like a strong push, often when least expected. One day he chanced upon Dennis Brimo dancing twist during Angelus out of the peripheral view of the moderator, his back towards the corridor. Bro. Ben’s well planted kick sent Dennis flat across his desk. Bro. Malachy succeeded him from our sophomore to the first half of senior year. You knew something was wrong whenever his face turned red as a beet so… cuedao ka hijo. Bro. Cajetan was intimidating and looked formidable as a Panzer tank. His habit of flexing his fingers into clinched fists and his Al Capone scar masked his gentler side. All three principal walked with phantom stealth and treaded the floor like nightshift hospital nurses.

Among our teachers in grade school was the venerable Mr. Juan Medrano, the first lay teacher in La Salle who had taught our parents. In high school we had both great as well as so-so teachers, all patient and parental. Among us classmates, we referred to them by pet-names we had given them: Botong, Lone Ranger, Apeng Daldal etc., yet not out of disrespect – cariňo brutal lang. Many classmates had pet nicknames too like: aso, ahit, baho, ngongo, gayot, tarugo, ipis, etc. Some of our professors must have had daily prescriptions for maintaining blood pressures; what with the classroom notoriety most of them had to go through each day, typical throughout high school. However this is not to overstate the case since even unruly classes were well-behaved under certain teachers. Majority of us took our education seriously with a few seeing nothing wrong with having some fun in class too.

The model students were well-behaved like Rhett Pleno who seemed destined to top the class; Jacques Schnabel was sharp as finely-honed Henckels cutlery, so was Tony Aguirre. Others excelled in their favorite subjects: Nonong Umali was undeniably a genius at math, likewise, James Vinzons; Bobby Tolentino an Einstein in Science. Rony Mayor, Darwin Labordo and Vic Arches were consistently above average in all subjects; some simply content to cruise along due to plain laziness or preoccupation with teenage matters. Had penmanship been the major grading criteria, then either Ben Tiong or I would have vied for class valedictorian.

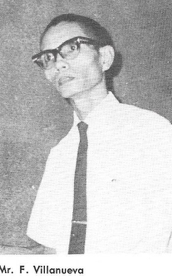

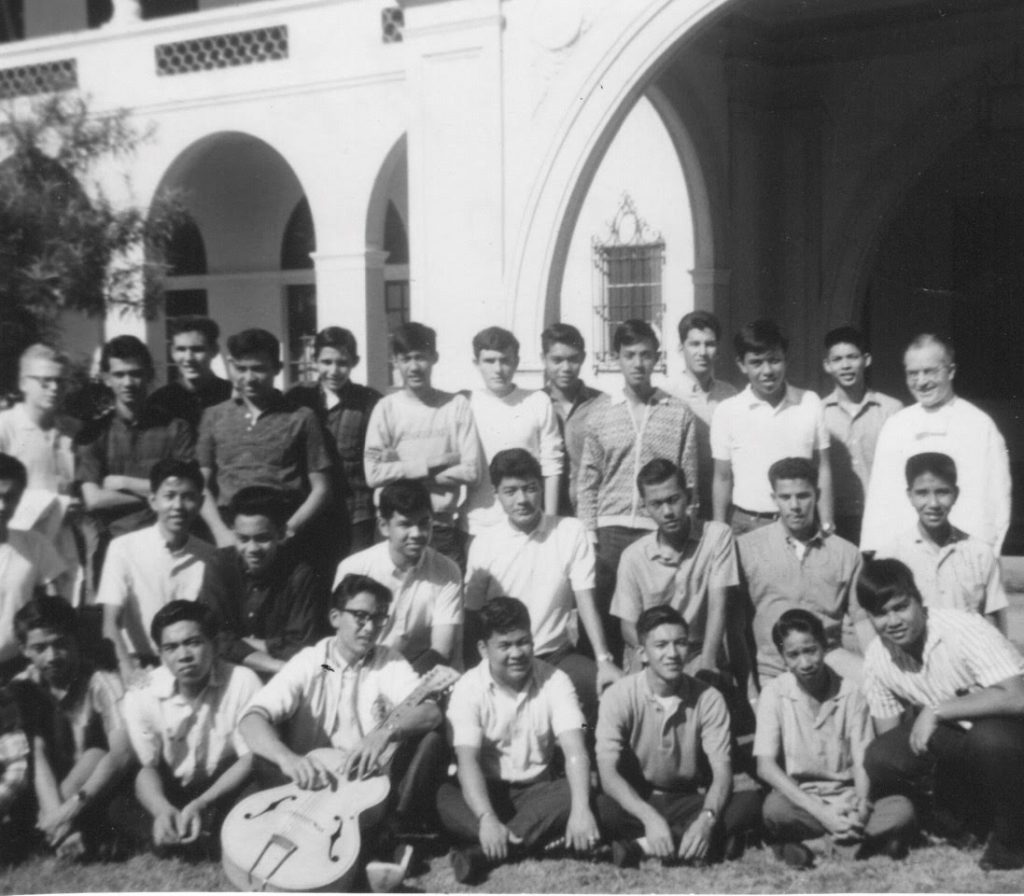

Mr. F. Villanueva

Reverend Brother Cajetan

Brother Benedict and Brother Malachy

The model students were well-behaved like Rhett Pleno who seemed destined to top the class; Jacques Schnabel was sharp as finely-honed Henckels cutlery, so was Tony Aguirre. Others excelled in their favorite subjects: Nonong Umali was undeniably a genius at math, likewise, James Vinzons; Bobby Tolentino an Einstein in Science. Rony Mayor, Darwin Labordo and Vic Arches were consistently above average in all subjects; some simply content to cruise along due to plain laziness or preoccupation with teenage matters. Had penmanship been the major grading criteria, then either Ben Tiong or I would have vied for class valedictorian.

Needless to say each managed with studies his own way. Richard Lopez was diligent in taking notes – jotting down everything on the blackboard including “Save.” Math was terra incognita for Archie Abad but he always had the correct answer, which puzzled Mr. Felipe Villanueva who could never figure out his graffiti-like computations. Babes Francisco made good use of the gridlines in his mathematics notebook to chart Jai Alai events and results, complete with each and every pelotari’s number and jersey color for every game. Chuck Buenaventura perfected the microfilm codigo. Jose Luis Crame’s barely audible whispers were undetectable, perhaps even by radar. Monchet Hidalgo was well behaved, attentive, participated in recitations, always prompt and neat in all his work, above suspicion, but left nothing to chance with his comprehensive codigos.

Smart alecks loved to elicit laughter with precisely timed comments; the masters of this art were Gerry Arabit, Mari Vargas, and Rene de la Fuente. Teachers could be amusing too and also provided the laughs: Mr. Salvador Calumno with his recycled stories about son, Junior, Mr. Tereso Lara and his “double zero,” and surely, Mr. Bobby Kraut, with his temper tantrums and OA facial expressions. Once, he paused in the middle of a lecture with an amused countenance fixated on a classmate (unnamed here) slouched deep in his seat, and nonchalantly digging into his nose. Mr. Kraut jolted him out his inattentiveness with, “How was your fishing?” and he slowly rose wondering what to say; while all around him were whispers of… “False”… “True”… “Yes…” “No”… until finally committing himself… “False, sir”.

There was almost never a dull moment in class. Quite often the misbehavior was confined to a small section in the classroom, generally undetected until unrestrained snickering and muffled laughter betrayed something rotten going on. Some teachers were quick to conduct an inquisition to such slight disturbances, while others let them pass as trivial. One lazy afternoon, Tony Arellano threw a toothpick he had used on his ears across two rows to an unsuspecting Tommy Lim, the missile landing on his desk. Tommy momentarily looked at it, then put it in his mouth.

Each day began with an inspection at the third floor landing by PNT officers, the Gestapos of our time who gave us demerits for anything out of regulation in our khaki gray uniform (styled by Ah Wong) or haircut; this meant having to report for Saturday drill. Late comers secured a late pass from Mr. Pacifico Galvez, our typing teacher who also moderated Jug Class, every Wednesday afternoon at 3:30 pm, fifteen minutes after dismissal. The Junior Police headed by Nonny Velez were exempted from late passes since they assisted the traffic cops in managing the flow of traffic during morning hours before classes and noontime dismissal. What’s admirable is they never demanded tong from the jeepney and bus drivers.

Jug class was like doing time in Purgatory. One-time tardiness meant having to solve a nine-digit by six-digit multiplication (hundred million x hundred thousand) and the answer in fantasticatillions added horizontally. A wrong answer meant staying until the correct answer was figured out. Two and three late tardy slips meant six and eight problems respectively. Slide rules and mathematical tables (no calculators then) were not allowed.

Those coming from the South Gate had the option of a short visit to the Chapel of St. Joseph (renamed Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament in 1991). It was a habit for a good number of us to drop in for a short prayer. We recall our Thursday confessions in the Chapel before every First Friday Mass in Grade School: often, our confessor-priests were Chinese Jesuits from Kuang Chi (Xavier) or from St. Jude Parish, who had fled China during Mao Tse Tung’s rise to power. Their heavy accents made it difficult for us to understand one another which put us more at ease in confessing.

Prayer played an important part of high school life; time in class was bookended by prayer, with all invocations ending in, “Live Jesus in our hearts… forever.” We were taught in grade school to affix JMJ at the top of all written work. Morning sessions in Grade School and High School were predicated with three mysteries of the Rosary and the remaining two at start of afternoon session. Breaks for recess and return to class, and dismissal for the day were prayer times too; the Angelus was the norm at noon.

We were told in Grade School that the sign of a True LaSallite was his rosary, and most of us carried one in the pocket. During the Silver Jubilee Mass of High School ’68 – the Last of the Mighty – in March of 1993 the chaplain asked the congregation of La Sallites whether they still carried their Rosaries. And to his surprise most everyone in the chapel, silver, gold, diamond jubilarians, and other La Sallites raised their rosaries for the chaplain to see.

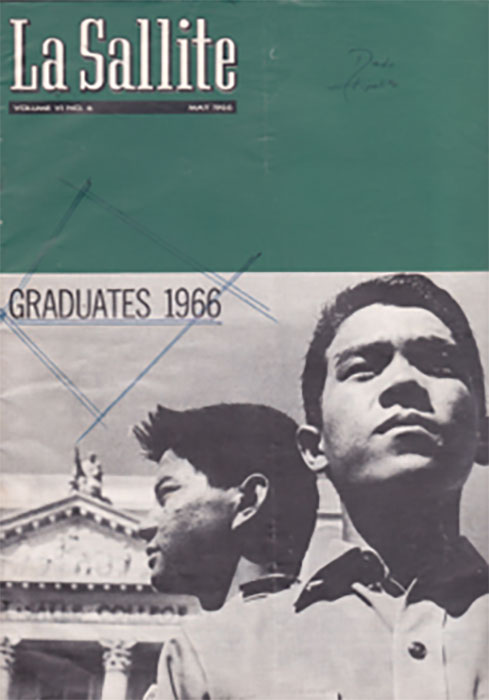

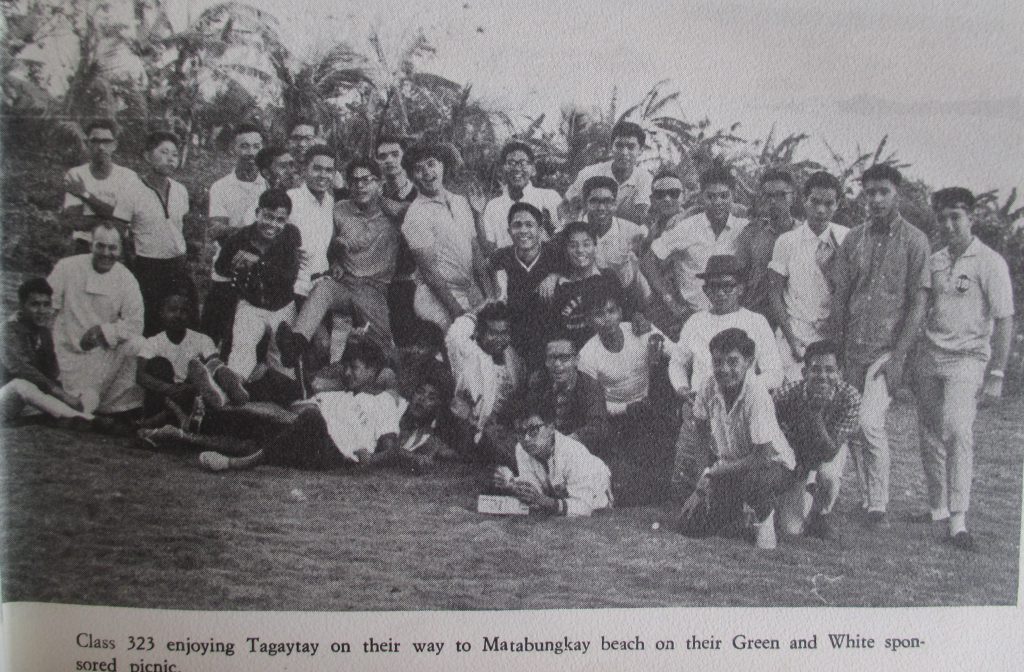

Our other activities included lab work in Biology, Chemistry, and Physics; typing, class, mechanical drawing, PE, extracurricular occupations like membership in school organizations and Christmas and newspaper drives.Two school publications were the LaSallite magazine, published every two months, and Green and White annual which gave us the opportunity of apprenticeship in print media.

Lito Buňag, our Art Editor for both publications went on to pursue a successful career in industrial arts. In senior year I was Photo Editor for both of publications; Digoy Fernandez being my editor-in-chief for the magazine, Chito Jaraiz for the annual. My ticket to entering Rizal Memorial for the NCAA games, and skipping drill was my camera, which often had no film during Friday PNT. Oh how the cadet officers, loved to preen and act candid every time I pretended to take pictures of them.

Being a PNT officer and trying to act militarily was difficult when facing friends. Buddy Jugo realized this when, as company sergeant, he was unable to restrain himself from blurting out “Balut” to Renato Zamora. Jimmy Brown and Tony Aguirre marched ahead of the PNT regiment with the corps colors, but never in cadence, owing to Tony’s two left feet. When I got drafted to the shore patrol platoon, my colleagues and I were privileged to skip drill; we skipped haircut inspection to look after the book bank and exempted class. Then one Friday before a big Saturday Assumption party we had all looked forward, Bro. Malachy surprised us one day with a hair clipper and proceeded to mow our sideburns. It does seem uncanny how principals somehow always managed to spoil your weekend.

There was almost never a dull moment in class.

We all anticipated the scheduled respite from our classes in the semester break, Christmas vacation and the summer Vacacion Grande. Recess and lunch break were the daily respite from class. At the canteen Mang Teroy and Vicente attended to us with the basics: sandwiches, soft drinks, milk and choco-drinks, candy. What could not be availed of was always found outside the gate in Pidiong’s pushcart – victuals for eating in class. Chewing gum was preferred since it could be stuck in the corners of our desks, adding to the layer of gums tacked on over the years.

Pranks included the thievery of gourmet sandwiches inside the classroom or a thumb tack on the seat. Surprisingly fights almost never ensued from these. A favorite mischief was crushing kantutay leaves from a wild vine that grew across St. Scholastica’s College along Leon Guinto Street – where one of the St. Benilde buildings now stands. Crushed on the blackboard, floor, or teacher’s platform it emitted a foul stench, very much like an un-flushed, maggot-filled toilet bowl and the odor lasted several minutes. The mischief was done during a break shortly before the bell rung and always disrupted class.

A yearly tradition was the planting of a whistle bomb at either of North or South wing latrines at approach of the Christmas vacation. The bomber placed the firecracker during the break lit by a cigarette or piece of katol to time the firecracker to explode during class hours; the explosion always drew approval from the classrooms. By the way, the ten gallon water tanks of those pre-war toilets were placed high up against the wall ten feet above – guaranteed to flush just about any product of constipation.

Our camaraderie developed around the school’s landmarks. Of these only the Marian Quadrangle remains; the Athanasius Gym, handball court, the old canteen and covered area are gone. Likewise gone is the handball court Dado Jose’s realm; where he was unbeatable at handball. At the time I had often wondered how the firemen of Paco Fire Station would have fared against him. But like any superstar, Dado too had a nemesis, Gerry Bulatao. We miss that landmark where Macky Dominguez and Gerry Sison practiced their tennis strokes occasionally. After college I played jai-alai there too with Bro. Franco; with our cestas (mine from Oyarzabal) we preferred playing the courts facing the north end where we could use the outer corridor walls for rebote.

Away from the classroom we had the library to research, play chess or siesta, or the Archers’ Nook across Taft and the billiard halls. To entice us to remain at campus, we were given the Senior Lounge were we could while the time away or take a nap, and a room near the chapel where we could play pool. Here Enos Siscar rule the roost, the billiards king whom we fondly called Minnesota Fats.

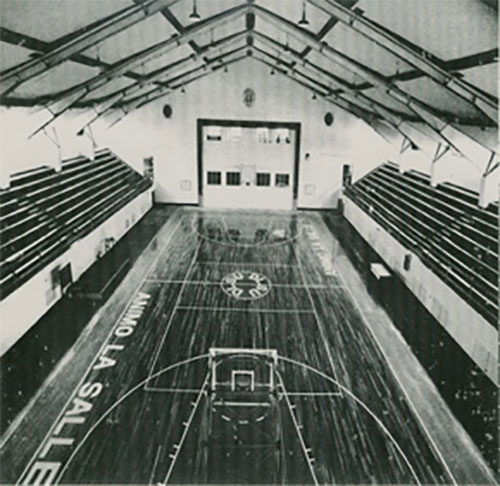

The Athanasius Gym was a preferred venue for many events: sports, rallies, final exams, PE classes, programs, graduation, etc. Outside its confines was an area by the estero called “Back of the Gym.” This was where irreconcilable differences were settled in fisticuffs, and ironically lasting friendships also forged. One day back in grade three Ricky Africa and Eddie Manalo decided the campus wasn’t big enough for them both and decided to settle their scores. BoyFeria and I were the referees.

We gave the signal and the “Thrilla” got underway, Ricky putting up his dukes a la Gentleman Jim, and Eddie weaving like Rocky Marciano. The two squared off eying each other intently like fighting cocks and circling slowly before finally trading blows with no one connecting, before Eddie lunged at Ricky and grabbed him by the waist. Falling to the ground they rolled in the macadam road raising dust – it had become a wrestling match! Suddenly someone yelled at us from the college end of the gym and Boy and I both took off in a run with Ricky and Eddie hot on our heels. The fight ended as soon as it had begun and the two became close friends.

The gym was very much a part of our lives. It was where we first sang the Alma Mater and Go La Salle in a corporate setting. The inspiration for the latter was from the movie Lilies of the Field starring Sydney Poitier, where the nuns sang it as Amen. Bro. Malachy was the source of both songs. Our class contribution to the varsity cheers was When La Salle Goes Marching In. Mari Vargas had “oomphed” it in his tuba during a game prompting trombonists Rene de la Fuente and Aris Cebrero to follow up, and the cheering section picked it up from there. The cheerleaders led by Gilbert Jose and basketball team captain Rey Bautista confided in later years how energizing “Go La Salle” and “When La Salle Comes Marching In” were during the games.

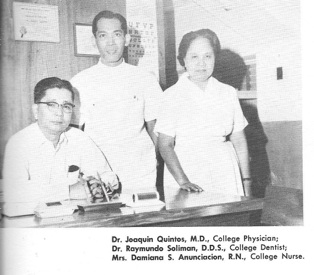

The bookstore, sports equipment, showers and school clinic were located in the recessed space, beneath the bleacher stands. Our physician was the mild mannered Dr. Joaquin Quintos whose paternal humor put us at ease during the yearly inoculations and vaccinations.

Back in grade school he had a fond way of calling some us camote; little did he know that one of the camotes, Dadito Hipolito, would eventually be his son-in-law, marrying the prettiest of his lovely daughters, Cory. After passing on to his heavenly home he was replaced by a relative of Boy del Prado – Dr. Francisco del Prado, an Jai-Alai aficionado, therefore a classmate of sorts at the Taft fronton. Completing the clinic personnel were Mrs. Damiana Anunciacion, a motherly nurse who would often say “Ano ang nangyari sa iyo hijo?” and the jokester dentist, Dr. Raymundo Soliman.

One of the most important features in school was the football field. During our 1991 silver jubilee, Brother Ben’s Alumni Office leaked out memoirs of my late father, Teodoro de Vera (HS’26) entitled, “A La Sallite Remembers,” where he wrote that what impressed him most about De La Salle was the international-sized football field. By our time the FIFA standard pitch had shrunk in size owing to the addition of St. Joseph’s building at its western end and the outside basketball courts along its northern flank. It was in one of these courts where, Jojo Mirasol patented his novel top of the foul-line layup, years ahead of Dr. J.

At any rate our field was still respectable in size. Football was the school’s sport and just about everybody played it; La Salle had won more varsity championships in football than any other sport. In those days we had a Messi – Xavi Ugarte a year ahead of us – who mesmerized everyone with his zigzagging around the pitch like a Porsche on a slalom track and could score from any angle.

Our class had its share of stalwarts: striker Bert Garcia, swift as a gazelle deadly accurate as Ronaldo or Raul. Bert also patented the Mano de Dios goal years ahead of Diego Maradona. Gabby la’ O, was tireless as a horse on the pitch and could play any position. Ronnie Ronquillo was our own Black Pearl with a keen instinct for goals. Gonzalo Hernandez was reliable in set pieces. Chuck Buenaventura was diminutive for a goalie but fearless like Valdes of Barca and had the anticipation of Buffon.

Intramural football during a heavy downpour was among the most fun-filled times we had in the football field. But we also found fun in other activities, PE, bonfires, and practice games. As a member of Varsity Softball, our coach Mr. Bobby Kraut put us through long hours of rigorous batting and fielding practice to prepare us for the NCAA games. Our last game against Ateneo at the La Loma baseball field was memorable. I was playing center field when the La Salle spelling was heard from a passing bus. Aboard were classmates en route to the Jesuit Sacred Heart Seminary in Novaliches for graduation retreat. The bus had slowed down and good Ole’ Jimmy Brown who was on board led the cheering.

The football field, or what’s left of it, is still our Field of Dreams; a hallowed ground of open space where every year, the past is reminisced in every De La Salle homecoming. No more will shouts of “Centra” … “Pasa” … “Escapada” … “Pa-a-a-sing Review” … and the satirical “to-o-o-on” following “Pla-to-o-o-o-on” be heard in these environs, except in our memories that echo our golden years of campus life and brotherhood of La Sallites.

Article was originally published in 2018. Written by Edgardo C. De Vera.